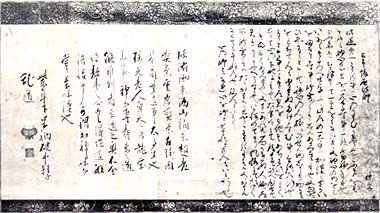

Letter of the Heart

kokoro no fumi

by Murata Shukō

Translation and further thoughts

by Adam Sōmu Wojciński

Forward

The ‘Letter of the Heart’ is the earliest known document on chanoyu as a spiritual art. It was written by Murata Shukō (1421(?)-1502), regarded as the person who transformed tea drinking from an aristocratic pastime to a Way for spiritual attainment. This document by the ‘Godfather of Wabi’ endures with timeless guidance for all who come into contact with the Way of Tea. In the letter, Shukō illuminates chanoyu as a sensually lived expression of the inner life of Buddhist practice; asserts that we can grasp aesthetic and moral ideas with striking vivacity through objects; encourages the pursuit of beauty in one’s immediate surrounds and harmonising this beauty with that found in foreign lands; notes that spiritual transformation works ‘at the heart’s ground’ beyond the ego/self; and compels a balance of humility, critical self-reflection and poise at all stages of the tea person’s development.

The letter is addressed to Furuichi Harima Hōshi (1452(?)-1508), a Buddhist priest and minor daimyō. Furuichi became a monk at Nara’s Kōfuku-ji temple before succeeding his elder brother as daimyō and head of the Furuichi family in the outskirts of Nara city. He was a keen patron and practitioner of the arts, particularly renga poetry, noh theatre, shakuhachi and chanoyu. In 1488, Furuichi requested detailed instruction in renga from the poet Kensai (1452-1510). Kensai responded by expanding notes he had made from the words of his teacher Shinkei (1406-1475). There are striking similarities in expression and content between this letter of Kensai’s and Shukō’s own letter to Furuichi. It is entirely possible that Furuichi showed Kensai’s letter to Shukō when asking him for like instruction on the deeper praxis of chanoyu. Upon reading Kensai’s letter on the essence of renga, we can imagine Shukō finding the words to illuminate what was in his heart regarding the Way of Tea.

The aesthetic and moral posture described in both Kensai and Shukō’s letters reflect the ideals of beauty of their time, ideas that seek beauty in the pathos of things and the sublime, while grounding morality in a deep listening to Nature. The unique move of Shukō is to articulate that a state of mind can be grasped in the material constitution of objects and that such objects can work on the spirit. This work happens at ‘the heart’s ground’ beyond the ego/self where the human being is connected to the ultimate reality of things. As one reaches maturity of insight across one’s art objects, self and source, the ‘chill and lean’ beauty of the Void unfolds throughout one’s practice. ‘It is here that one truly uncovers beauty that moves.’

The reader of this translation is directed to the masterful translation by Dennis Hirota included in volume 22 of the Chanoyu Quarterly (1979). Hirota preserves the terse tone of the original letter (whereas I prefer to unpack the dense kanji compounds with a more poetic style). Hirota’s supporting essay and notes are essential reading. Following his comprehensive research is the gift of translated sections of the ‘Shinkei Sozu Teikin’, Kensai’s original letter to Furuichi on the spiritual posture of renga. Hirota’s work explores the historical context of Shukō’s letter. My point of departure is the enduring meaning of the Letter of the Heart for both contemporary and future practice.

Through the translation process, inspiration came to attempt a modern day letter from the heart. The hope was to highlight the enduring relevance and evolution of the meaning of the original through poetry rather than prose. Talk about ‘immodesty’! Over 500 years have passed since Shukō inked his brush to write the original letter. The timeless themes he articulated are now pursued by tea people world-wide. As we welcome the year 2020, we are reminded that before long, chanoyu may have more practitioners outside than inside Japan. At this juncture, one is compelled to review the core teachings in Shukō’s letter while advancing and deepening the original insights for our time.

- Adam Sōmu Wojciński, 2020

Letter of the Heart

Furuichi Harima Hōshi,

In the Way of Tea, nothing will hinder you more than immodesty(1) and the heart’s attachment to self(2). Begrudging masters of the Way and looking down on beginners is superficial and wasteful. One should rather seek the least word of those wise in the Way and endeavour to guide beginners as far as possible.

Of the utmost importance for this Way is dissolving the boundaries between Japanese and foreign art objects. One must attend to this with care.

Further, these days those inexperienced in the Way are quick to take up Bizen and Shigaraki wares, claiming an advanced and deepened understanding of the ‘chilled and withered’ aesthetics they embody. All the while the elite Tea community mocks these eager yet presumptuous hopefuls, creating a disgraceful state of affairs.

An aesthetic sensibility for the ‘chill and withered’ means acquiring fine pieces with view to knowing their savour in the marrow-bone. Then from the heart’s ground one advances and deepens so that all after becomes chill and lean. It is here that one truly uncovers beauty that moves.

When one does not yet fully understand the beauty of things(3), it is crucial that one does not adopt commonly held views without scrutiny. However cultivated one's manner, a painful self-awareness of one's shortcomings is crucial. Remember that self-assertion and attachment are obstructions. Yet the Way is unattainable if there is no self-esteem at all. A dictum of the Way states: “Become heart's master, not heart-mastered”.

Shukō

(1) 我慢 gaman, or ahaṃkāra in Sanskrit and Pali, means ‘conception of I’, ‘egotism’ or ‘arrogance’.

(2) 我執 gashū, or ātmagraha in Sanskrit, is the ‘clinging to self’ or ‘conception of self’. Attachment to a separate self is considered the fundamental ignorance, the root cause of suffering.

(3) The word used is ‘dōgu 道具’. Therefore Shukō is therefore talking about utensils/art objects for tea.

古市播磨法師 珠光

比道、第一わろき事ハ、心のかまんかしやう也、

こふ者をはそねミ、初心の者をハ見くたす事、一段無勿躰事共也、

こふしやにハちかつきて一言をもなけき、又、初心の物をはいかにもそたつへき事也、

比道の一大事ハ、和漢之さかいをまきらかす事、肝要肝要、ようしんあるへき事也、

又、當時、ひゑかるゝと申て、初心の人躰かひせん物、しからき物なとをもちて、人もゆるさぬたけくらむ事、言語道断也、

かるゝと云事ハ、よき道具をもち、其あちわひをよくしりて、心の下地によりてたけくらミて、後までひへやせてこそ面白くあるへき也、

又、さハあれ共、一向かなハぬ人躰ハ、道具にハからかふへからす候也、

いか様のてとり風情にても、なけく所、肝要にて候、たゝかまんかしやうかわろき事にて候、又ハ、かまんなくてもならぬ道也、

銘道ニいわく、心の師とハなれ、心を師とせされ、と古人もいわれし也