The 100 Poems of Chanoyu

The original Japanese language 100 Poems of Chanoyu are composed in a poetry style known as ‘waka' or ‘tanka’. Waka poems limit the poet to 31 syllables, with the syllables arranged in five lines of 5, 7, 5, 7 and 7 syllables to each respective line. To illustrate:

稽古とは / keiko to wa

一より習い / ichi yori narai

十を知れ、 / jyū wo shire,

十より歸る / jyū yori kaeru

元の其の一 / moto no sono ichi

Practice starts from ‘1’

and continues through to ’10’

Each step is learnt well

before returning to ‘1’ -

Where new understanding lies

This format makes the poems mnemonic devices for the fundamental philosophy and practical teachings of chanoyu. At the time of Jōō, Rikyū, Oribe, etc., it was forbidden to take or refer to notes in the tearoom during practice. This is still so today for some teachers. Creating rhythmic poems capturing the fundamental teachings of chanoyu enabled the student to recall the teachings at crucial moments during practice. In this form, the teachings are also readily transmittable to future generations. The 100 Poems of Chanoyu stands as proof of this method. More than any other manuscript from the formation period of chanoyu, the hundred poems is the most widely used text, still employed today by teachers and students across all schools of chanoyu.

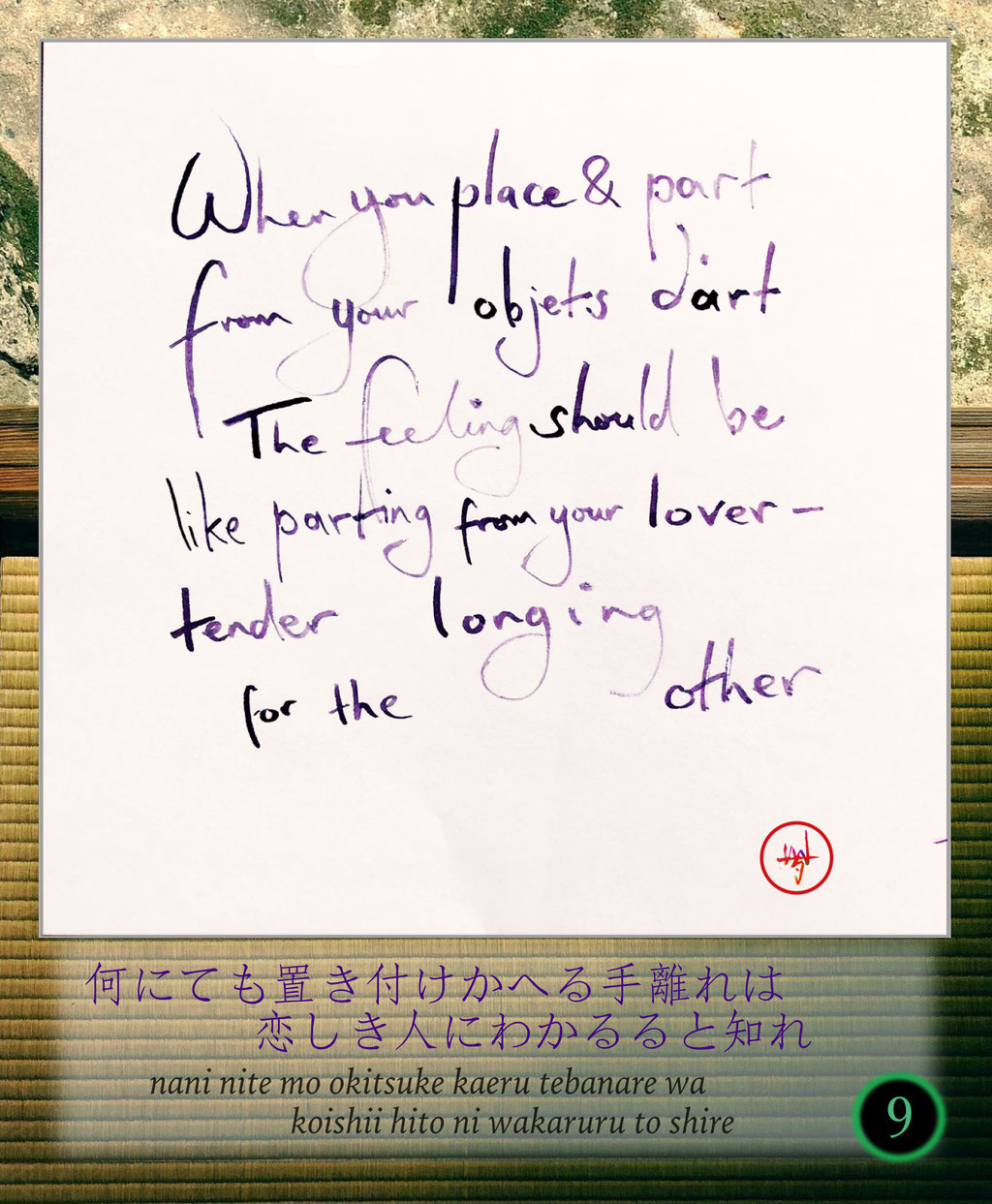

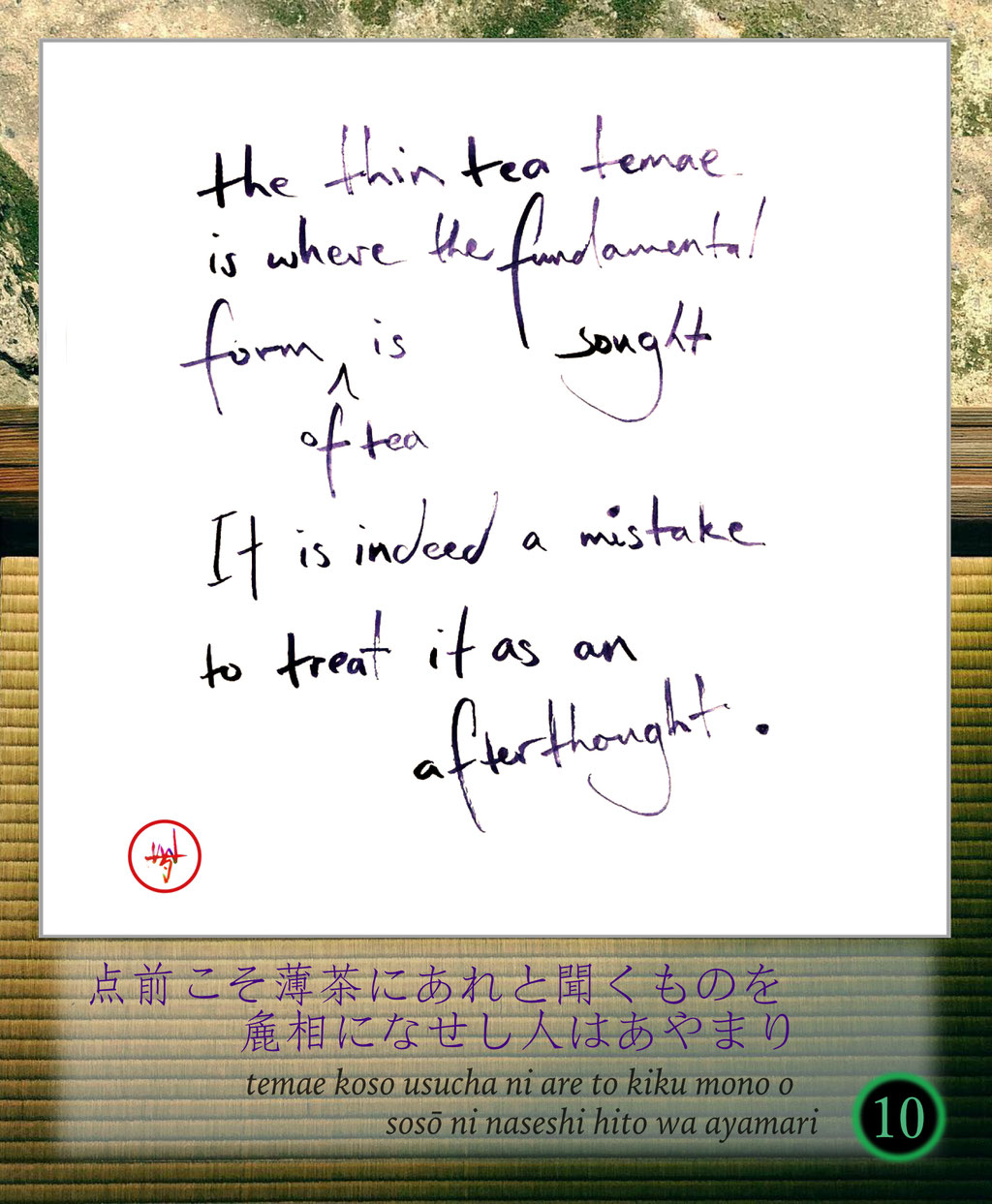

In English translations of the poems, a meaning-based approach has been employed to relay their wisdom. I think, however, that translations that accord to the rhythmical pattern of 31 syllables should be preferred. With English translations following the 'waka' style, the English poems will be as readily committed to memory and as useful in people’s practice as the Japanese originals were for masters like Jōō, Rikyū, Oribe, Sōko and Enshū.

The teaching of chanoyu in the Momoyama (1568-1603) and early Edo (1603-1868) periods was very different than the structured environment of today’s practice. In the sixteenth century, there were no organised schools of chanoyu like there are today. Practitioners would gather around a respected master who was deeply versed in the teachings of chanoyu. This person acted more like a curator of an esoteric tradition rather than a teacher. In this way, they offered a critique on people’s performance of tea rites and their setting of a tea room, steering of a tea gathering, etc., rather than dictate specific teachings that could not be distorted.

When one wanted to enter a chanoyu study environment, they would seek and introduction to a senior practitioner and ask for acceptance into their group. In the case of powerful feudal lords, they often requested guidance from a tea master via written correspondence. Feudal lords were commonly avid students of chanoyu, but as their status and duties prevented them from attending group practices, they would receive guidance through letters and transcriptions of core teachings.

Once accepted into a group, the student would simply observe for many months, most often for years, before physically preparing tea before another person. Learning was by observation until the novice was finally invited to practice a tea rite in front of the group. Around the time of this initial step of maturity, the master would copy out a version of the 100 Poems of Chanoyu and give it to the student to commit to memory. The student would then perform tea rites at practice with the hundred poems as their compass. The master continued critiquing the student in their practice until eventually giving them permission to perform chanoyu outside of practice and before real guests. The student would progress further and further and the master may have at some point transmitted the esoteric teachings of chanoyu that have roots on the continent, and in the tearooms of legendary figures like Ikkyū Sōjun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, Murata Shukō and Nōami.

In such a learning context, the 100 Poems of Chanoyu are of central importance for the novice. In the practice of chanoyu today, one starts by learning the ‘correct’ way to perform guest etiquette such as tea drinking, bowing, viewing utensils, etc. Then when one starts practicing actual tea rites, their concern focuses on remembering the steps of the intricate procedures rather than the fundamentals that underlie them. Sooner or later, the hundred poems become relevant and a study of these fundamentals begins (fundamentals that are shared across all schools).

It must be noted that the 100 Poems of Chanoyu would be copied and given to students without a specific title. Over two centuries after their original composition, the 100 Poems of Chanoyu started to be referred to as the ‘Rikyū Hyaku Shu 利休百首’ in Japanese, or ‘Rikyū’s Hundred Poems of Chanoyu' in English. The first instance of the poems appearing under Rikyū’s name is probably when Sōshitsu Gengensai, the 11th Grandmaster of the Urasenke school, wrote a version of the poems on a fusuma (sliding partition) of a tearoom at the headquarters of Urasenke. At the end of his composition he entitled the poems “The Hundred Poems Taught by Rikyū Koji”「利休居士教論百首歌」(Rikyū Koji Kyōron Hyaku Shuka). Since then, practitioners of Urasenke have come to know the poems under the more familiar title “Rikyū’s Hundred Poems of Chanoyu”「利休百首」(Rikyū Hyaku Shu). Tankōsha, Urasenke’s publishing company, has published multiple editions of the poems under the same title, further spreading the sense that the authorship of these poems was by Rikyū.

I have chosen to title the collection more generally under ‘chanoyu’ rather than Rikyū’s name as Rikyū did not compose all of the poems. It is generally accepted that one of Rikyū’s teachers, Takeno Jōō, composed the majority of the poems. Jōō was a trained classical and renga (linked-verse) poet who mostly worked in precisely the waka format of the 100 Poems. Rikyū would have no doubt added several to the collection, as would have other tea masters of the day. As such, attributing a single authorship to the collection is misleading. The poems come from a time when no organised schools of chanoyu existed, yet strikingly, the poems are still relevant for all schools of chanoyu created since the Edo Period. Let us tea people celebrate this shared practical wisdom in the tea room, and the shared moral and spiritual sensibility that this collection has transmitted through generations, and will do for generations to come.

- Adam Sōmu Wojciński, 2017

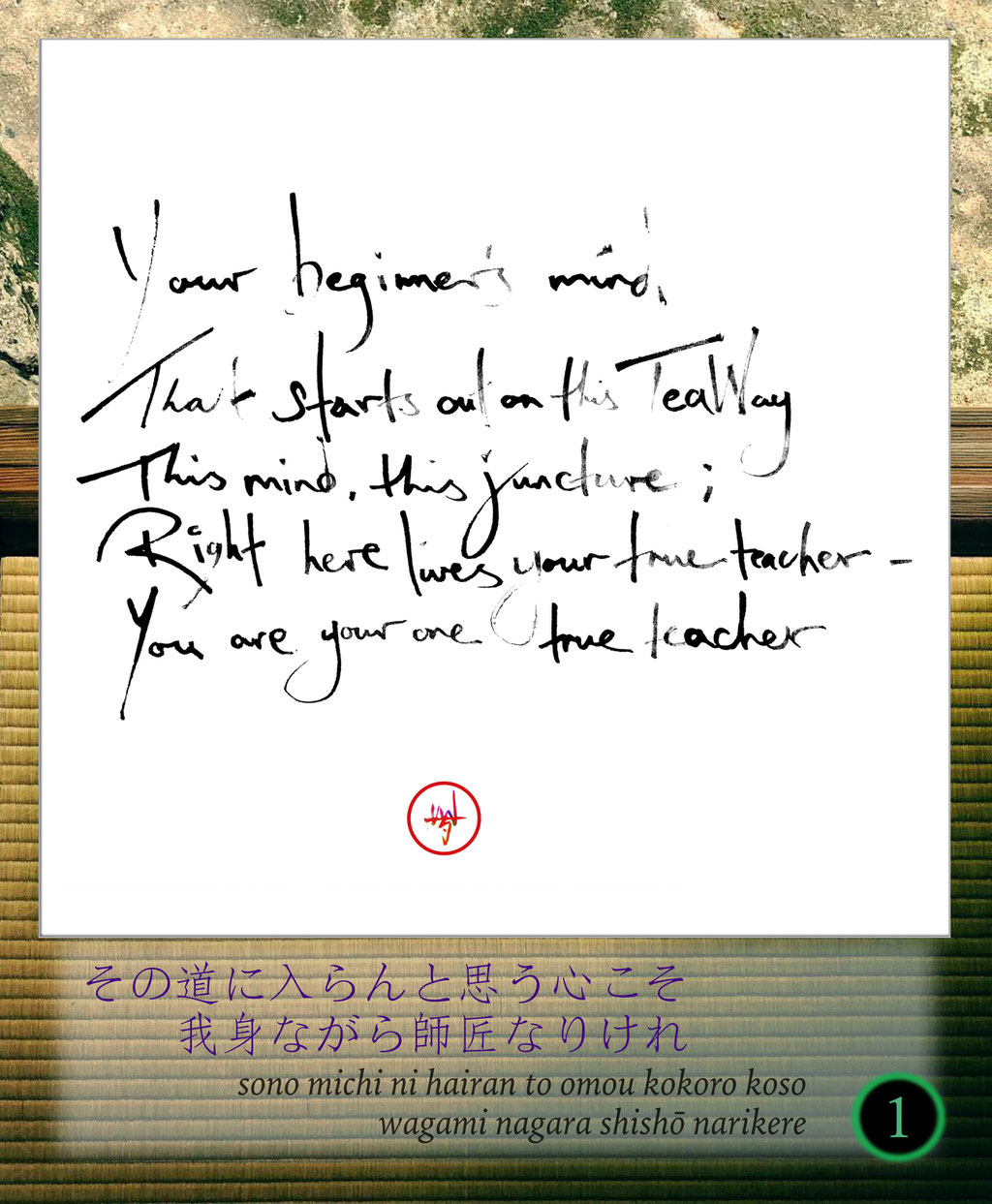

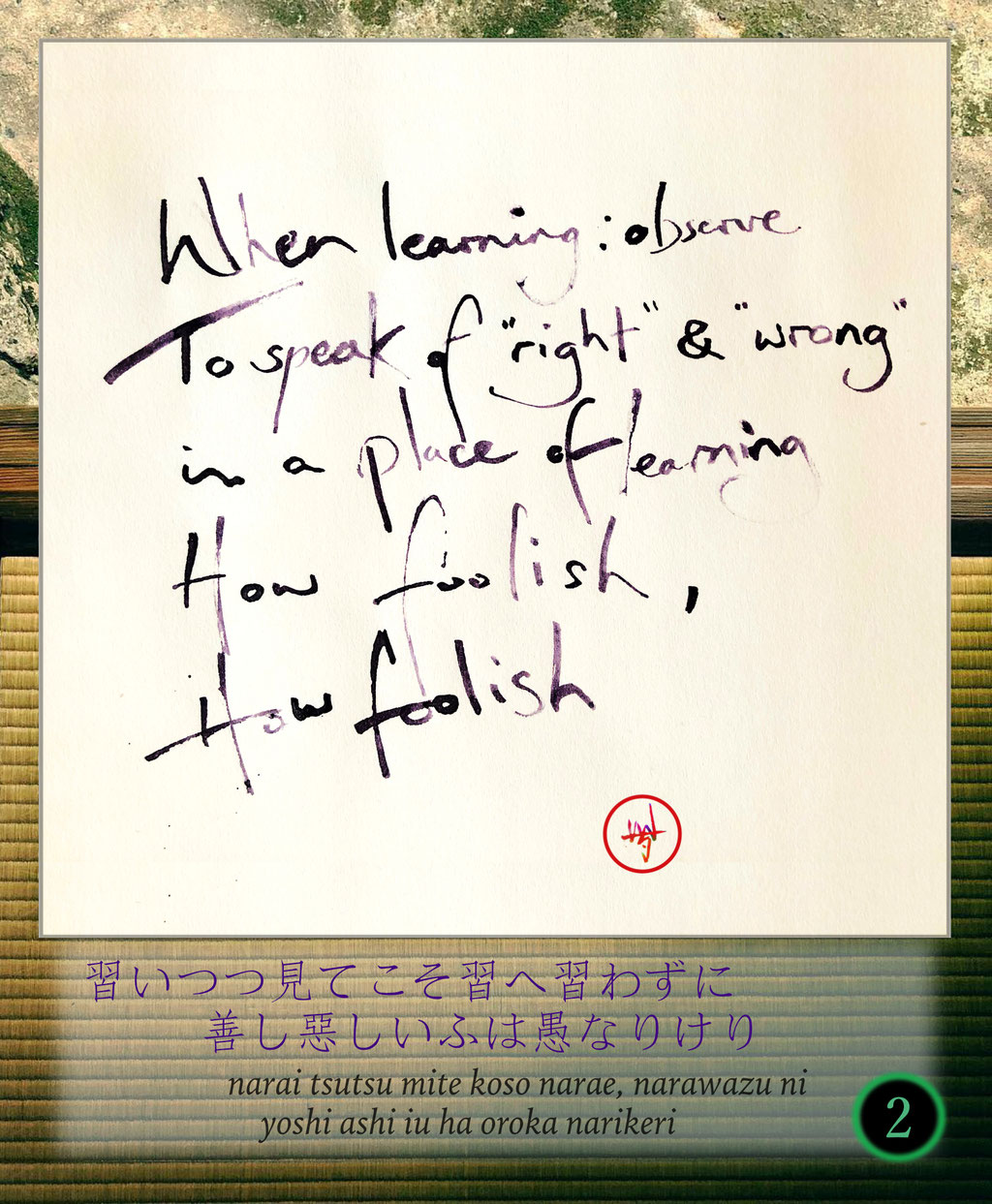

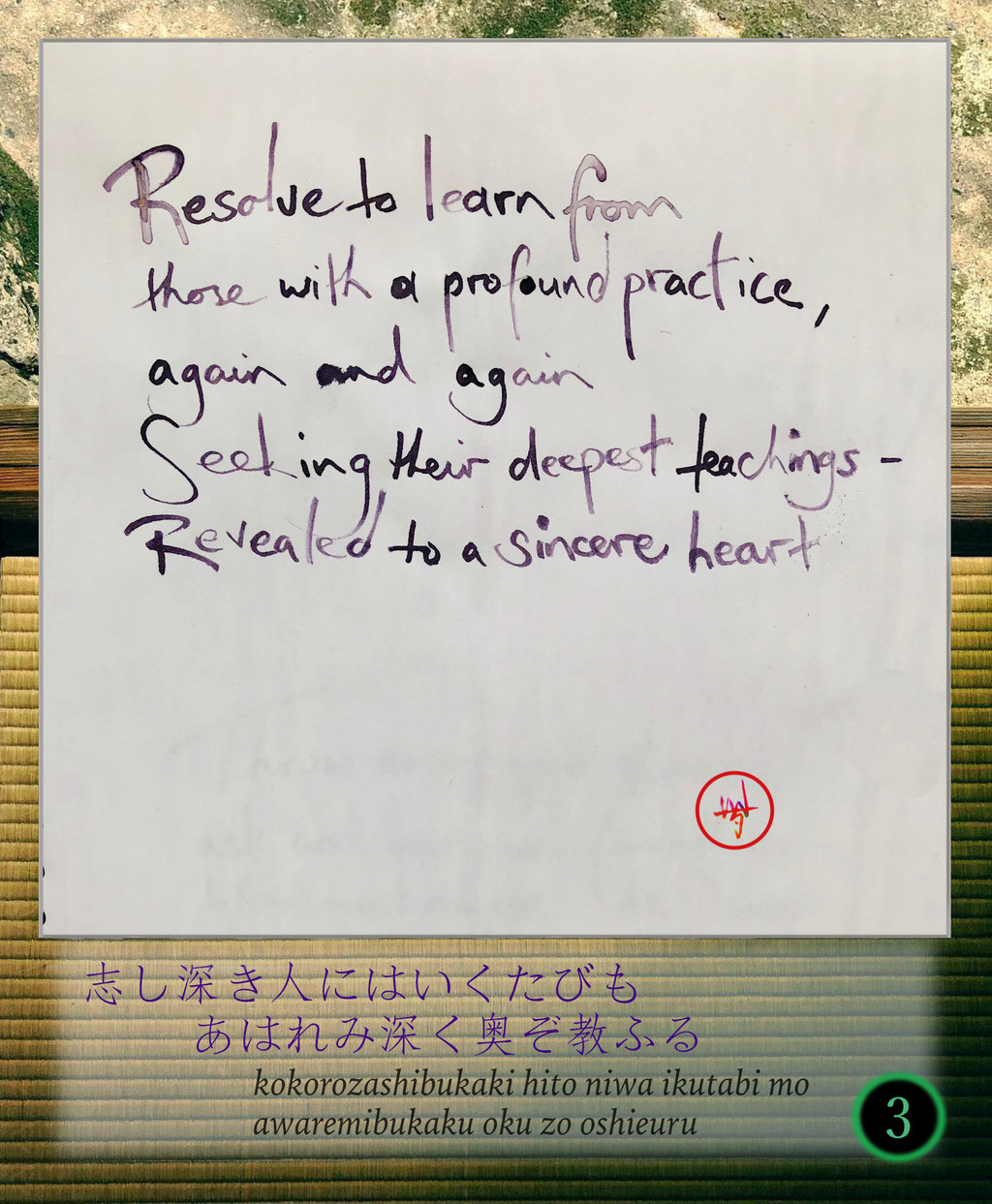

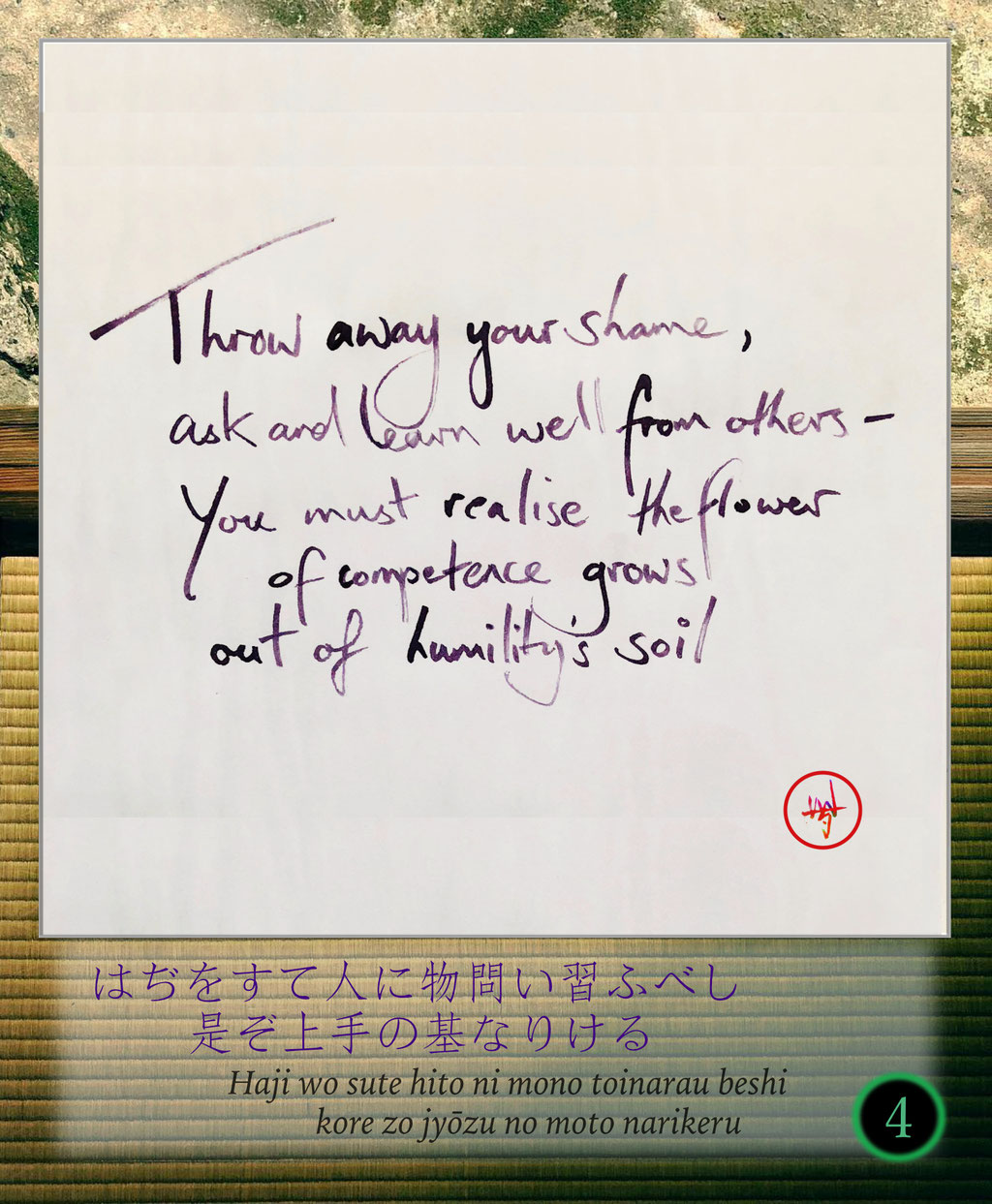

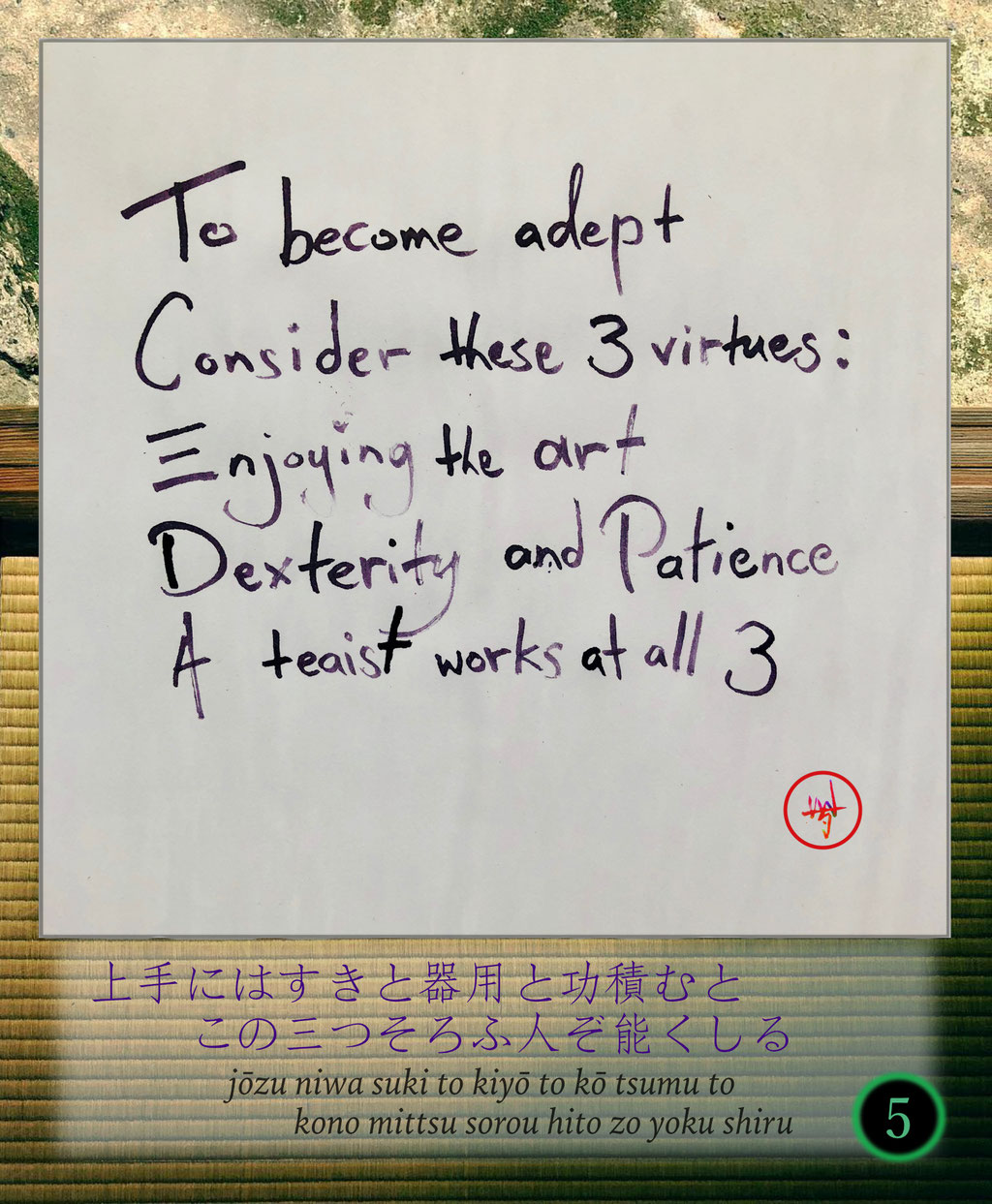

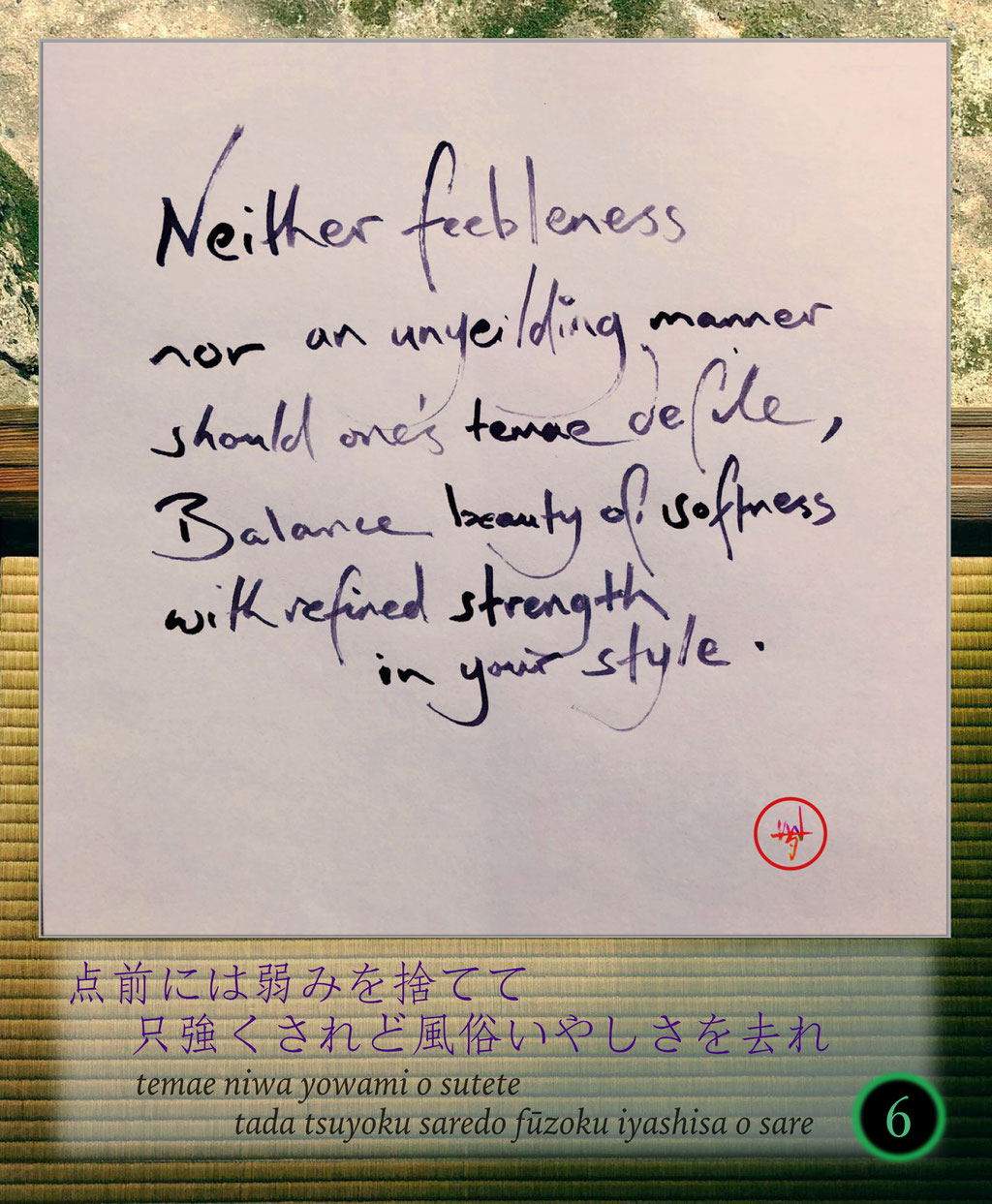

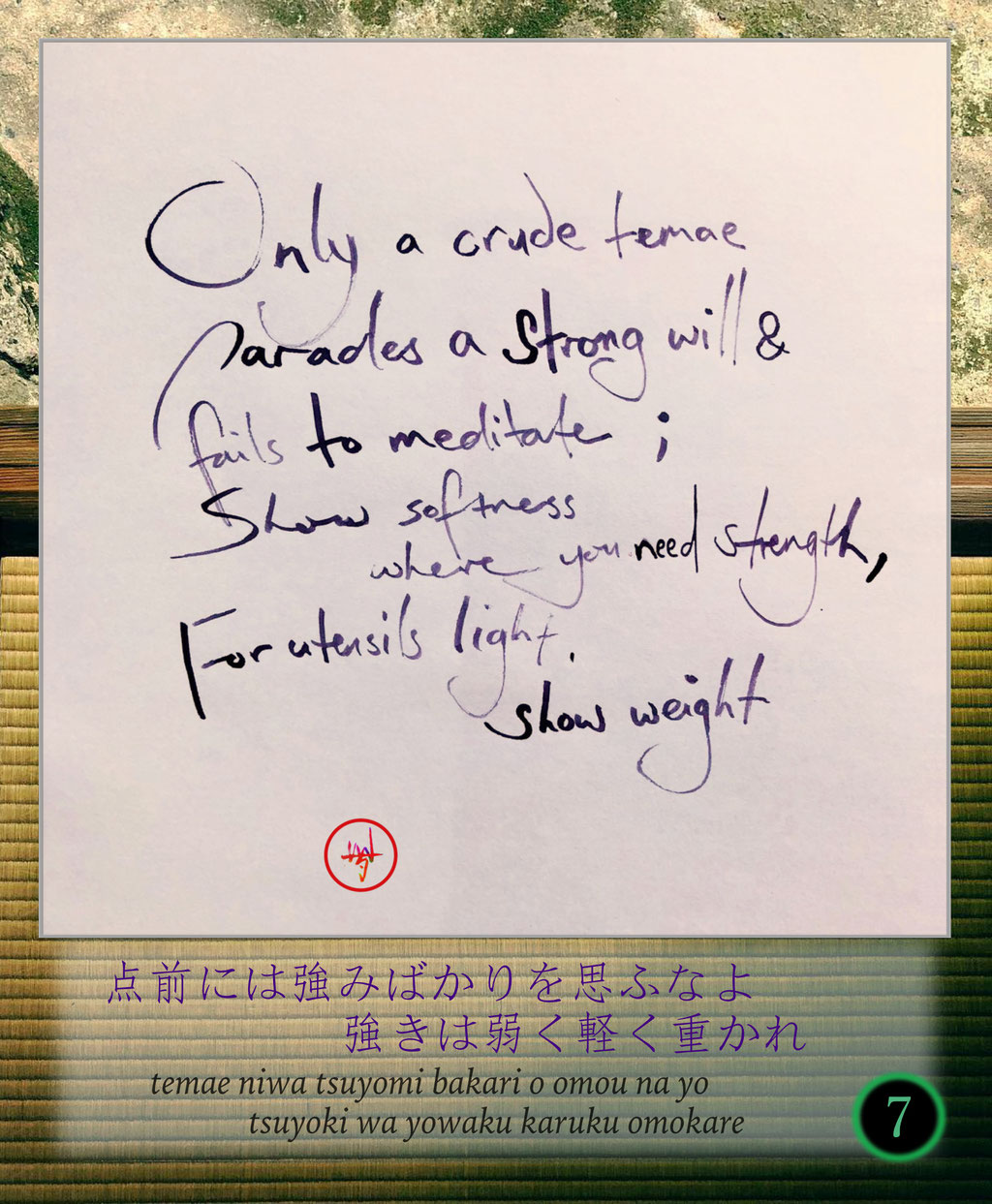

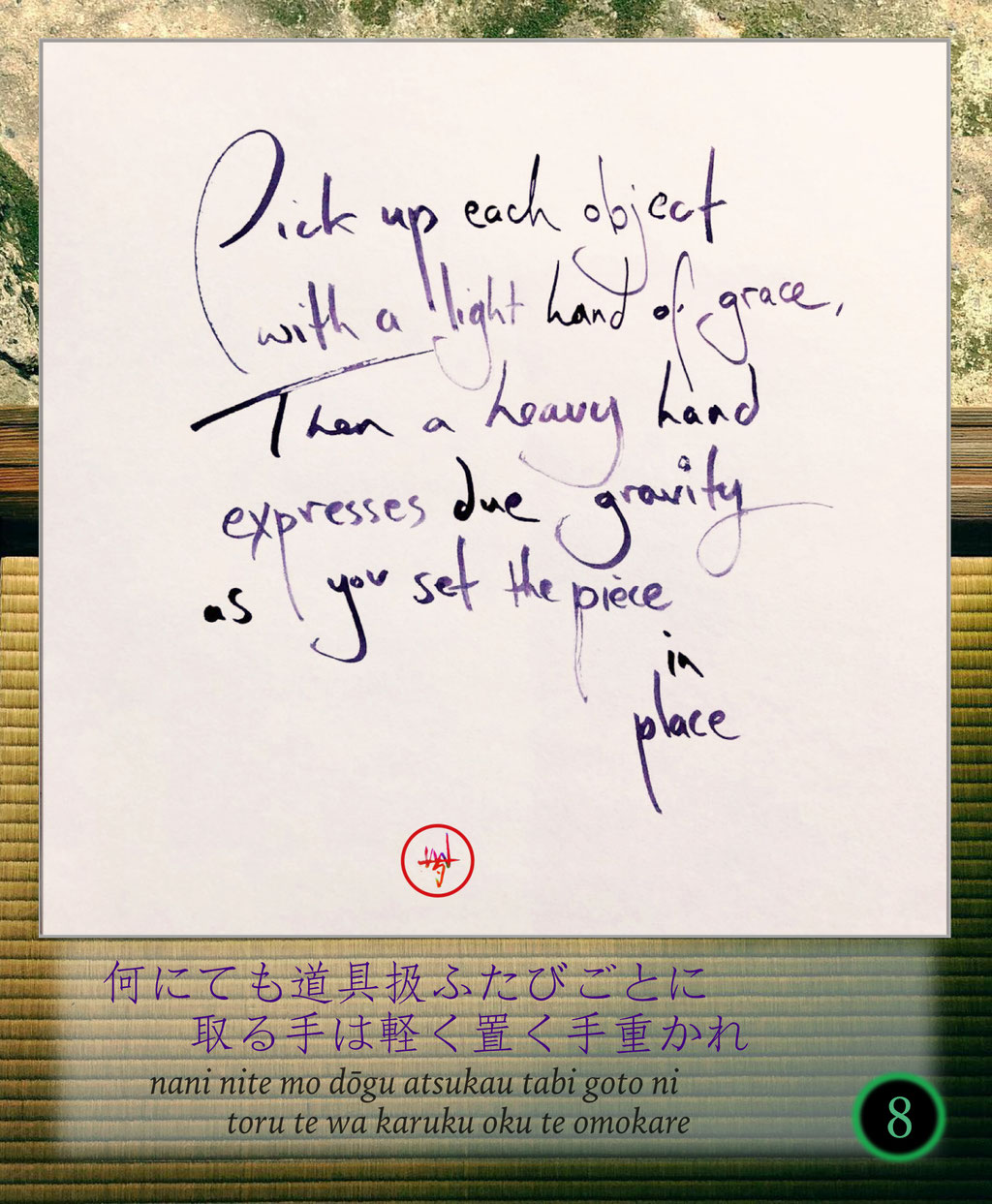

The first 10 poems are below. I may revise the translations in the future before publication. For more information on this translation project, please see this page.