Poetic Names for Tea Scoops 茶杓の銘 Chashaku no Mei

Poetic Names (mei 銘) for Tea Scoops (chashaku)

Poetic names for chashaku or 'mei 銘' are poetic names given to tea scoops (chashaku) that metaphorically celebrate, or conceptually associate with the individual characteristics of a chashaku.

The poetic name of the chashaku is revealed to the guests at a key conversation point between host and guest towards the end of a tea gathering. The mei caps off the poetical medley of the objets d'art used on the particular occasion by tying in with the seasonal, memorial or other theme of the day, heightening the feeling created by the host through their arrangement of tea utensils and art works. The mei thus becomes a strong factor in the overall ambience of the tea gathering. It leaves a lingering image of beauty with the guests as they take their leave and reflect on the gathering in the hours and days after.

Many people would be familiar with the naming of abstract paintings, the playful naming of their car, even a favourite teapot or other everyday items. This is shared across cultures. The practice of formally naming art works and precious ritual items with a 'mei 銘' has existed in Japan since the Heian Period (794 to 1185).

The character '銘' (mei・poetic name) means to carve a name into metal or rock. Overtime the character has gathered a wider meaning. It has come to mean something written on one's heart or soul; something of such profound meaning that it cannot be forgotten. It is also a name that speaks the spirit of a thing. Poetic names (mei) are given to various objects used in tea: a tea bowl, ceramic vessel, tea caddy, a unique type of saké, unique type of confectionary, unique type of matcha tea, and of course, a chashaku. An appropriate mei captures the essence of the object, seeping through its texture to its core.

The inspiration behind the naming of a chashaku and other tea implements may draw from one or a combination of the following:

1. Metaphorical mei

Metaphorically alluding to the individual characteristics and aesthetic appearance of the object.

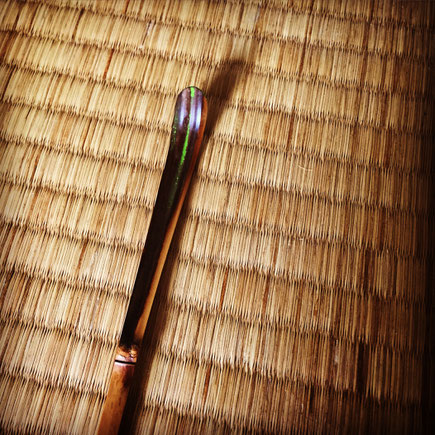

For example, this chashaku is named 'Nomad's Flute', taken from a Rinzai Zen capping phrase in the Shin Zengoshū.

The node at the end (Jōō's favoured style) and the pores on one side remind me of a flute. The scooping end opens up wide and deep, hungry for cha. In the Shin Zengoshū is this capping phrase:

"Oh, the plaint of the nomad's flute is heartbreaking.

Seated guests gaze at each other, tears run like rain."

胡歌一曲斷人腹

坐客相看淚如雨

(koka ikkyoku hito no harawata o tatsu,

Zakyaku aimite namida ame no gotoshi.)

The whole capping phrase can be used as the poetic name. But from the beautiful scene, 'nomad's flute' stands out to become the abbreviated name. When one informs

guests of the poetic name at the end of the tea rite, it would be wise to recite the full capping phrase as well as the abbreviated name and remark how the name was chosen.

2. Historical mei

Poeticising the history or origin of the object.

Example: 'Teki-gakure' (Waiting for the enemy) chashaku by Ueda Sōko

Made in the first year of the Genwa period, 1615.

During the Battle of Kashii in the early stages of the Summer Campaign of the Siege of Osaka, though all other supporting forces had withdrawn, Sōko refused to withdraw his own troops and held ground waiting for the enemy to approach. As he waited, he discovered fine bamboo in a bamboo grove and carved two chashaku with his small sword. This pair of chashaku were named 'Teki-gakure' (Waiting for the enemy).

3. Seasonal mei

Capturing the feeling of the season at the time the chashaku was crafted.

Example: the mei of the chashaku to the left is 'Ghostly Winter Wood 冬木立 fuyukodachi'. It was carved from a twig from a fallen winter branch, the maker finding the last line of this haiku appropriate:

Leafless tree, ax hew,

Such vibrant scent fills the air!

Ghostly winter woods

- by Buson, my own translation

4. Playful mei

Punning, using wit or joke to name the object in association with its character or history.

For example, the chashaku on the far left was named 'kamakiri' (praying mantis) and the second from the left 'imomushi' (green caterpillar), based on a combination of the look of the chashaku and the different personalities of the two people who carved them.

Image thanks to Jun Tanimura: https://www.instagram.com/p/BEqXjVrFTAb/?taken-by=leoniki

5. Poem mei

Writing or giving a full existing poem as a name for the object based on the impression the object gives (my favourite). Kobori Enshū is credited for being the first teaist to start naming chashaku with full poems based on his impression from the chashaku. These are called 'utamei 歌銘' (poem name).

One example of an 'utamei' is below. The story goes that Enshū crafted a chashaku with a single whole in the bamboo. As the summer rains were approaching and the sky at night was becoming more and more clouded, he savoured the last glimpses of the stars at night before the summer rains took over the night sky. Seeing this one tiny hole in the chashaku reminded him of a single star from a break in the cloud. He then composed this poem for the chashaku:

星ひとつ

見つけたる夜

のうれしさは

月にもまさる

五月雨のそら

- 小堀遠州

Hoshi hitotsu

Mitsuketaru yoru

no ureshisa wa

Tsuki nimo masaru

Samidare no sora

Lo, a single star

A jewel glimpsed through cloudy night

As the moon ages

The summer rains draw nearer

Stars and sky fade to my heart

- my own translation

One significant factor in the naming culture of tea equipage is the rich history of poetry and poetry compilations in Japan. Japanese words are pronounced with even weight on each mora (≈ syllable), to an almost mathematical rhythm. This characteristic may have contributed to the creation of distinctly Japanese forms of metrical poetry that started to appear from the Middle Ages, such as 'waka' poems which are limited to five lines of 5, 7, 5, 7 and 7 mora (similar to syllables) on each respective line. For example:

わが背子が

来べきよひなり

ささがにの

蜘蛛の振舞ひ

かねてしるしも

- 古今集

waga seko ga

kobeki yoi nari

sasagani no

kumo no furumai

kanete shirushimo

Tomorrow's diary:

A visit from my lover,

under blue-gold sky.

So writes this spider at twilight,

weaving my dream into night.

- from the Kokinshū, my own translation

Renga (collaborative linked poems) evolved out of Waka. One person would compose the first three lines called 'hokku' and the other collaborator would compose the last two lines (renku). Later the hokku became an independent form on its own and was called haiku. As per the opening stanza of a waka, a haiku is composed of three lines with 5, 7 and 5 syllables respectively:

斧入れて

香におどろくや

冬木立

- 蕪村

ono irete

ka ni odoroku ya

fuyukodachi

Leafless tree, ax hew,

Such vibrant scent fills the air!

Ghostly winter woods

- by Buson, my own translation

Before the representative arts of Japan such as tea ceremony, ikebana, calligraphy and incense appeared, even prior to noh theatre, poetry was the most highly regarded art form of antiquity. Poetry collections were widely read and studied among the elite classes (notably court nobles, the samurai class and wealthy merchants). The leaders of chanoyu (Japanese tea ritual) in its formative years were deft renga poets. The fundamentals of the art of tea were even taught in waka verses. Captured in 31 syllable poems, the core teachings of the art are easier to remember and internalise into the unconscious. Not only for teaching purposes, the tea masters' love of poetry led them to animate the proceedings of a tea gathering with poetical expression, exemplified in their use of hanging poetry scrolls and naming chashaku, tea caddies, tea bowls, fresh water containers and flower vases. Tea masters harvested these exquisite and meaningful mei 銘 from their rich literary tradition and poetry collections. Such collections are the Manyōshū (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves 万葉集, compiled around 759 - 800), the Kokinshū (Old and New Poetry Collection 古今集, compiled 890-920) and the Shinkokinshū (New Collection of Old and New Poems 新古今集, circa 1439). These are still a major source of mei 銘 today as well as more recent poets such as Bashō, Buson and Issa.

Great literary works such as the Tale of Genji (Genji no Monogatari 源氏の物語) are also rich sources of poetic names. Together with waka and haiku, such literary works are studded with 'kigo 季語' or 'seasonal words'. Kigo are used in waka, haiku and the collaborative linked-verse poetry form of renga, to indicate the season referred to in the stanza. Often two to four syllables, these words carry a strong linguistic register relative to their length. This register is one reason a poetic name for a chashaku rings so profoundly in a tea gathering. The utterance of the mei conjures up idealised visions of seasonal phenomena and nostalgia, romanticising the ambience in the tearoom, enhancing the seasonal or spiritual theme of the gathering. For example, the seasonal word in the above Buson haiku is 'fuyukodachi 冬木立' (ghostly winter wood). In the mind of a Japanese speaker, this word conjures up the image: 'a winter wood, trees standing like skeletons, seemingly dead, but with an implicit sense of the dormant life under the bark patiently waiting for spring'.

As an example from another culture, while reading Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, I came across the word 'puhpowee' from the Aboriginal Canadian Anishinaabe people. According to Kimmerer, 'puhpowee' means 'the force which causes mushrooms to push up from the earth overnight'. A gem of a poetic name for chashaku if I ever heard one. This is a fitting seasonal word (kigo) for Autumn, the season of mushrooms.

Silent eruption

Black night, white morn',

black soil, white 'shroom puhpowee

by Sōmu Wojciński

The last example demonstrates something of great importance for chanoyu as a global art form: its associated arts need not be exclusively Japanese. Poetic names for chashaku are but one way disparate cultures can come together through the vessel of chanoyu, deepening our understanding and aesthetic appreciation of foreign arts, languages and cultures. Poetic names (mei 銘) can be drawn from the poetry, literature, and language of any culture. To make this aesthetic play successful, in preparation for a tea gathering it would be worth the host's while to memorise the full poem or verse, the author and historical context from where the poetic name, Japanese or other, was harvested. By following the guidelines for naming chashaku above, practitioners of chanoyu can create their own lists of mei 銘 ringing with rich, cultural beauty for the ear, intellect and mind’s eye.

- - -

In the Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter pages are examples of poetic names fitting for these seasons. The Zen Words page lists words from Zen and esoteric Buddhist practice that can be used as mei in any season. The Zen Words usually have a ‘heavier’ register than the seasonal words and are therefore often used in the thick tea (koicha) session of a tea gathering. A ‘lighter’ seasonal word would then follow for the chashaku used in the thin tea (usucha) session. It is my wish that this ever-growing collection of mei 銘 enriches the practice of chanoyu for practitioners the world over.