Become a Patron of Adam's Translation Project

Adam's translation project is explained here and on his Patreon page

Translation project:

・Old Manuscripts from the Formation Period of Chanoyu

・Ueda Sōko Tradition History and Manuals

Adam Sōmu Wojciński, official English translator for Ueda Sōkei (16th Grandmaster for the Ueda Sōko Tradition) and the head of Adamu Shachū, is conducting an ongoing translation project to translate:

1. old manuscripts from the formation period of chanoyu, centring on Furuta Oribe's chanoyu; and

2. writings and publications on the history, aesthetics and procedures of the Ueda Sōko Tradition of Warrior Class Chanoyu.

The following is a current list of major titles he is currently translating or has completed. An explanation of each title follows the initial list.

1. Question and Answer with Furuta Oribe

- notes from a student of chanoyu in the early Edo Period

Status: 90% at August 2022

Status: Translation and commentaries complete, not published.

3. Furuta Oribe's 100 Lines of Chanoyu (3 versions)

Status: Translation complete, not published.

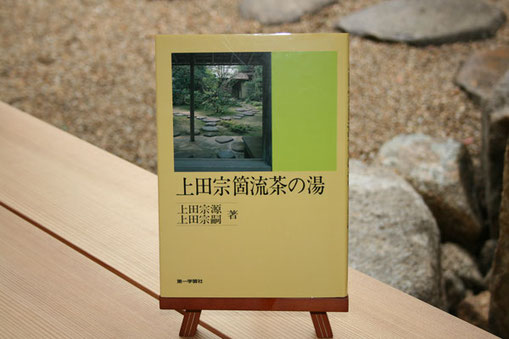

4. Ueda Sōko Tradition of Tea Introductory Manual

Status: Translation complete, not published.

5. The Ueda Sōko Tradition of Chanoyu - Advanced Manual

Status: 95% at May 2021

6. Pearl Among the Clouds by Ueda Sōkei

Status: Complete, Published.

Learning the Way of Tea with Furuta Oribe

notes from a student of chanoyu in the early Edo Period

An Audience with Furuta Oribe

notes from a student of chanoyu in the early Edo Period

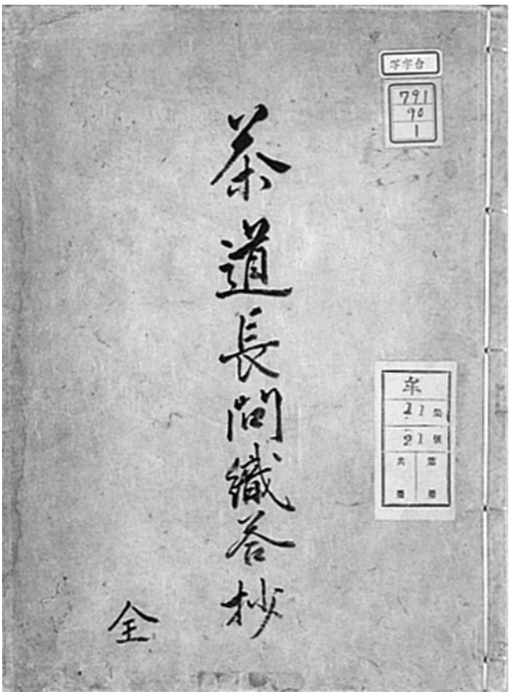

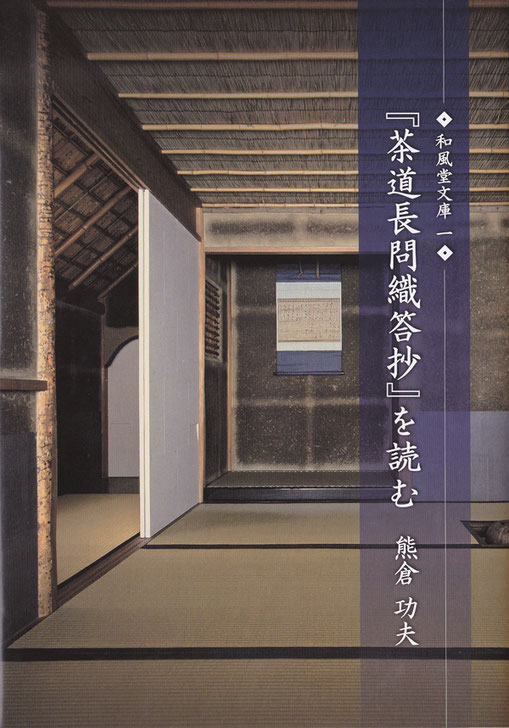

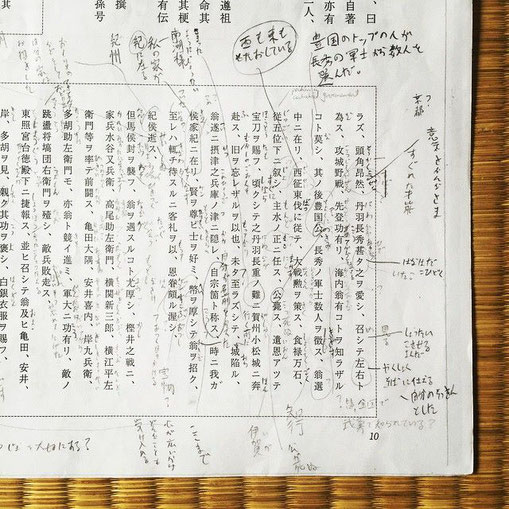

茶道長問織答抄 (sadō chōmon shokutō shō)

Of deep interest for researchers and advanced chanoyu practitioners of all schools.

As the name of this book suggests, this old manuscript of chanoyu is a compilation of notes on the teachings of chanoyu transmitted by Furuta Oribe. The compilation was made under the auspices of the Daimyo (feudal lord) of the Domain of Wakayama, Asano Yoshinaga (1576-1613). The person to have direct dialogue with Furuta Oribe and compile notes of his teachings on behalf of Yoshinaga was Ueda Sōko.

This manuscript is extremely valuable for learning the true chanoyu of Furuta Oribe. It is also a manuscript of great significance in the history of chanoyu as it is the oldest example of a dedicated student-teacher relationship. That is to say it shows that Ueda Sōko was solely dedicated to learning chanoyu from Furuta Oribe and no other teacher, something without precedent in documents prior to this one.

This manuscript has had multiple names including “A Written Account of Keichō Era Chanoyu” (慶長御尋書 Keichō O-kiki-gaki) and "Sōho's Written Accounts of an Audience with Furuta Oribe" (宗甫公古織江御尋書 Sōho-kō Furuori e O-tazune Sho). Sōho 宗甫 is the buddhist name of Kobori Enshū, founder of the Enshū Ryū of Chanoyu. This manuscript was previously accredited to Kobori Enshū until the original manuscript was discovered in the Ryukoku University Library. From the source text, it is clear the original author was Asano Yoshinaga.

This manuscript was composed between 1604 to 1612 (9th - 17th years of the Keichō Era), precisely the years Furuta Oribe was the leading tea master in the country, and his most active years in the art.

With Furuta Oribe in the prime of his chanoyu life, and Asano Yoshinaga as one of the most powerful feudal lords (ōdaimyō) in the country, their busy lives would have made it impossible for them to meet frequently. The practical solution to the transmission of chanoyu from Oribe to an eager Yoshinaga was to have Yoshinaga’s own delegate tea master, Ueda Sōko, act as a go-between for the two parties. Ueda Sōko attended Rikyū’s chanoyu practice as a student before becoming a student of Oribe. He therefore had the knowledge to readily comprehend and interpret Furita Oribe’s teachings for Yoshinaga. The studious work of Sōko is evident in this compilation of Oribe’s direct teachings.

When we think of Furuta Oribe’s style of chanoyu, we think of extremely liberal, even brash antics within the intimate setting of the tea room. However, this manuscript paints a very different picture. It shows Oribe as being concerned with minute details, even to the point of fussing over trifles. Could this be Oribe a symptom of Oribe lamenting over his popularity and the pressures of serving the Court and highest powers of the country? A loss of personal freedom countered by obsessing over details towards his students? Whatever the explanation, the figure that appears in this manuscript is a contrast to the very human side of Oribe we glean from history. This, along with the numerous other revelations that line the ‘Learning from Furuta Oribe’ manuscript makes compelling reading for advanced practitioners and researchers of chanoyu.

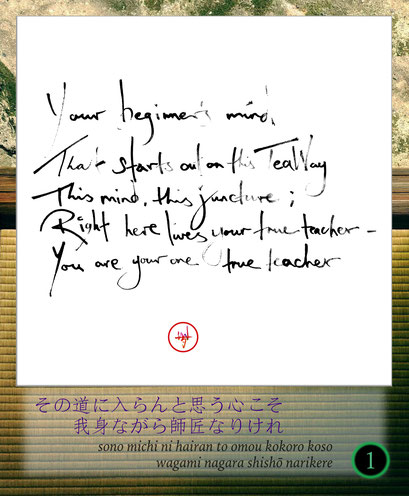

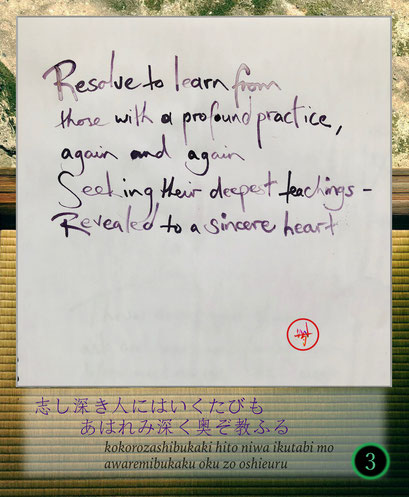

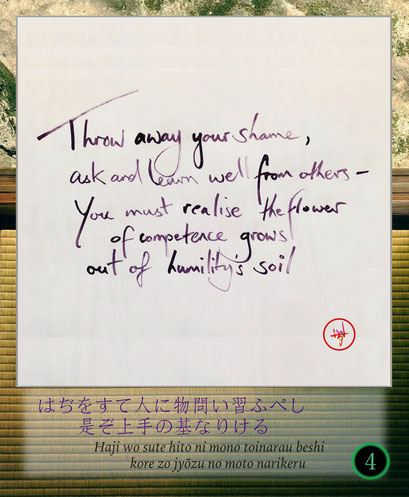

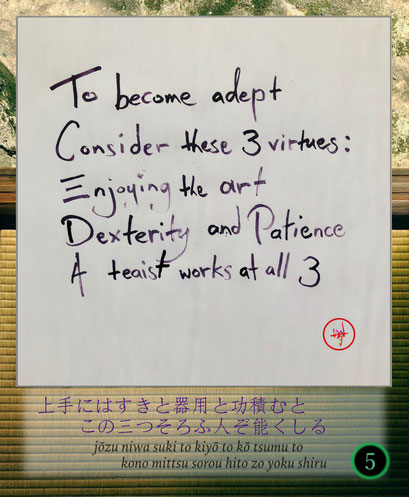

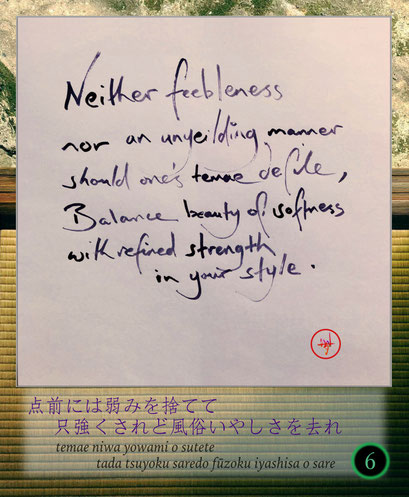

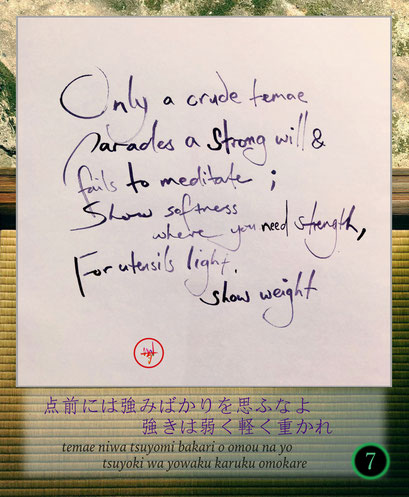

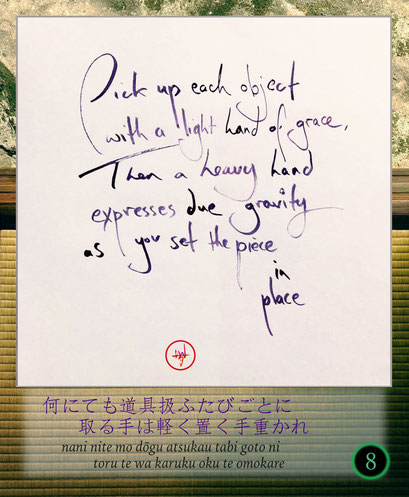

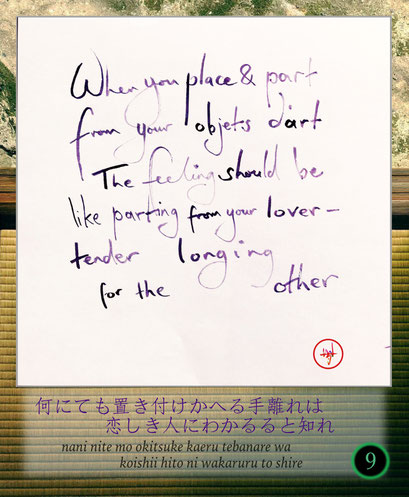

100 Poems of Chanoyu

The original Japanese language 100 Poems of Chanoyu are composed in a poetry style known as ‘waka' or ‘tanka’. Waka poems limit the poet to 31 syllables, with the syllables arranged in five lines of 5, 7, 5, 7 and 7 syllables to each respective line. To illustrate:

稽古とは / keiko to wa

一より習い / ichi yori narai

十を知れ、 / jyū wo shire,

十より歸る / jyū yori kaeru

元の其の一 / moto no sono ichi

Practice starts from ‘1’

and continues through to ’10’

Each step is learnt well

before returning to ‘1’ -

Where new understanding lies

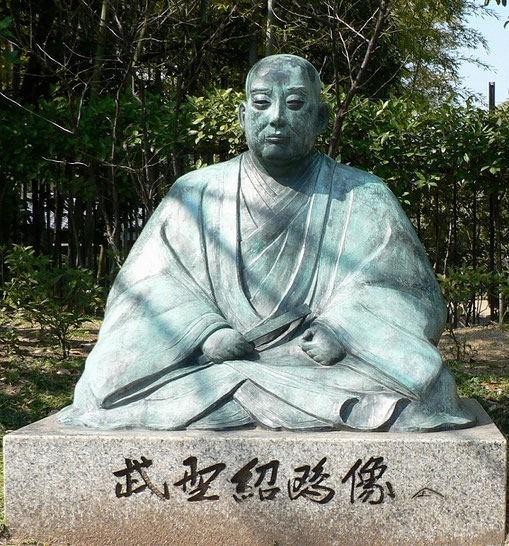

Image of Takeno Jōō by ja:user:田英

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ATakenoJoo.jpg

This format makes the poems mnemonic devices for the fundamental philosophy and practical teachings of chanoyu. At the time of Jōō, Rikyū, Oribe, etc., it was forbidden to take or refer to notes in the tearoom during practice. This is still so today for some teachers. Creating rhythmic poems capturing the fundamental teachings of chanoyu enabled the student to recall the teachings at crucial moments during practice. In this form, the teachings are also readily transmittable to future generations. The 100 Poems of Chanoyu stands as proof of this method. More than any other manuscript from the formation period of chanoyu, the hundred poems is the most widely used text, still employed today by teachers and students across all schools of chanoyu.

In English translations of the poems, a meaning-based approach has been employed to relay their wisdom. This translation attempts to be the first English translation that accords to the rhythmical pattern of 31 syllables. The translations are all in the ‘waka’ style. With this approach I hope the English poems will be as readily committed to memory and as useful in people’s practice as the Japanese originals were for masters like Jōō, Rikyū, Oribe, Sōko and Enshū.

The teaching of chanoyu in the Momoyama (1568-1603) and early Edo (1603-1868) periods was very different than the structured environment of today’s practice. In the sixteenth century, there were no organised schools of chanoyu like there are today. Practitioners would gather around a respected master who was deeply versed in the teachings of chanoyu. This person acted more like a curator of an esoteric tradition rather than a teacher. In this way, they offered a critique on people’s performance of tea rites and their setting of a tea room, steering of a tea gathering, etc., rather than dictate specific teachings that could not be distorted.

When one wanted to enter a chanoyu study environment, they would seek and introduction to a senior practitioner and ask for acceptance into their group. In the case of powerful feudal lords, they often requested guidance from a tea master via written correspondence. Feudal lords were commonly avid students of chanoyu, but as their status and duties prevented them from attending group practices, they would receive guidance through letters and transcriptions of core teachings.

Once accepted into a group, the student would simply observe for many months, most often for years, before physically preparing tea before another person. Learning was by observation until the novice was finally invited to practice a tea rite in front of the group. Around the time of this initial step of maturity, the master would copy out a version of the 100 Poems of Chanoyu and give it to the student to commit to memory. The student would then perform tea rites at practice with the hundred poems as their compass. The master continued critiquing the student in their practice until eventually giving them permission to perform chanoyu outside of practice and before real guests. The student would progress further and further and the master may have at some point transmitted the esoteric teachings of chanoyu that have roots on the continent, and in the tearooms of legendary figures like Ikkyū Sōjun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, Murata Shukō and Nōami.

In such a learning context, the 100 Poems of Chanoyu are of central importance for the novice. In the practice of chanoyu today, one starts by learning the ‘correct’ way to perform guest etiquette such as tea drinking, bowing, viewing utensils, etc. Then when one starts practicing actual tea rites, their concern focuses on remembering the steps of the intricate procedures rather than the fundamentals that underlie them. Sooner or later, the hundred poems become relevant and a study of these fundamentals begins (fundamentals that are shared across all schools).

It must be noted that the 100 Poems of Chanoyu would be copied and given to students without a specific title. Over two centuries after their original composition, the 100 Poems of Chanoyu started to be referred to as the ‘Rikyū Hyaku Shu 利休百首’ in Japanese, or ‘Rikyū’s Hundred Poems of Chanoyu' in English. The first instance of the poems appearing under Rikyū’s name is probably when Sōshitsu Gengensai, the 11th Grandmaster of the Urasenke school, wrote a version of the poems on a fusuma (sliding partition) of a tearoom at the headquarters of Urasenke. At the end of his composition he entitled the poems “The Hundred Poems Taught by Rikyū Koji”「利休居士教論百首歌」(Rikyū Koji Kyōron Hyaku Shuka). Since then, practitioners of Urasenke have come to know the poems under the more familiar title “Rikyū’s Hundred Poems of Chanoyu”「利休百首」(Rikyū Hyaku Shu). Tankōsha, Urasenke’s publishing company, has published multiple editions of the poems under the same title, further spreading the sense that the authorship of these poems was by Rikyū.

I have chosen to title the collection more generally under ‘chanoyu’ rather than Rikyū’s name as Rikyū did not compose all of the poems. It is generally accepted that one of Rikyū’s teachers, Takeno Jōō, composed the majority of the poems. Jōō was a trained classical and renga (linked-verse) poet who mostly worked in precisely the waka format of the 100 Poems. Rikyū would have no doubt added several to the collection, as would have other tea masters of the day. As such, attributing a single authorship to the collection is misleading. The poems come from a time when no organised schools of chanoyu existed, yet strikingly, the poems are still relevant for all schools of chanoyu created since the Edo Period. I therefore present the ‘100 Poems of Chanoyu’ in their English waka form for the first time to celebrate the shared practical wisdom in the tea room, and the shared moral and spiritual sensibility that this collection has transmitted through generations, and will do for generations to come.

Furuta Oribe's 100 Lines of Chanoyu

Image by: M-sho-gun https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AFuruta_Oribe02.jpg

Rikyū’s Precepts of Chanoyu Transmitted by Furuta Oribe

織部百ヶ条

There are numerous versions of Rikyū’s precepts of chanoyu with more or less the same contents. These precepts are not to be confused with the ‘100 Poems of Chanoyu’ (also know as ‘Rikyū’s 100 Poems of Chanou’). The 100 Poems of Chanoyu are just that: waka poems embodying the teachings of the early master. Rikyu’s Precepts of Chanoyu are a collection of concise notes, not in poetic form, that aim to instruct and be a reference to students. The majority of the versions in existence are copies of copies and have various titles. This is because the original practice was to simply copy and pass on the teachings rather give them a specific title. The recipient of the document often gave their version a name of reference and it is for this reason some of Rikyū’s precepts have come to be know as ‘Oribe’s 100 Precepts of Chanoyu’ or ‘Oribe’s 100 Lines of Chanoyu’, among others. The versions that came to (wrongly) bear Oribe’s name were those that Oribe himself copied and passed on to students, presumably from a copy given to him by his teacher, Rikyū. This is despite a note in the postscript that the contents were originally transmitted from Rikyū.

Of the versions in existence known under the title ‘Oribe’s 100 Precepts’, there are three versions of particular interest. The short name of reference of these versions are:

1. The Tokyo National Museum manuscript

2. The Kōshoji Temple manuscript; and

3. The Kurita-shi manuscript.

One shows a correction from ‘Oribe’s 100 Precepts’ to simply ‘The 100 Lines of Sadō’「茶道百首」. Two is the only teaching document on chanoyu in Oribe’s own handwriting still in existence. The third is the only version that could be justifiably called ‘Oribe’s Precepts’ as is appears to be his own version of the precepts by differing considerably from the multiple, homogenous version in circulation.

Tokyo National Museum manuscript

This manuscript is a transcription of teachings ascribed to Furuta Oribe made in the mid-Edo Period. The cover title is ‘Chanoyu as Transmitted by Furuta Oribe’「古織伝」. The title above the 100 precepts is ‘Furuta Oribe’s 100 Precepts’「古田織部正殿百ヶ条」and the precepts are composed on 10 sheets of Mino hanshi paper. Despite the name, there are 112 precepts. At the time of the transcription, a revised title ‘100 Precepts of Sadō’「茶道百首」has been added in red ink next to the title ‘Furuta Oribe’s 100 Precepts’「古田織部正殿百ヶ条」. This suggest the transcriber was aware that the precepts could not rightly be attributed to Oribe.

Kōshoji Temple manuscript

The Kōshoji Temple manuscript is the only teaching document on chanoyu known in existence to be in Oribe’s original handwriting. It is presently stored at Kōshoji 興聖寺, Oribe's family temple in Kyoto. The Kōshoji scroll is housed in a wooden box made after Oribe’s time. On the face of the box is the inscription “Book of Chanoyu Written by the Hand of Furuta Oribe”「茶之湯書織部筆一」. The scroll is composed of twelve pages with 107 seperate precepts in total. There are two distinctive features of this manuscript. First, the order of the precepts in this version of Oribe’s own hand is very different from the order of other versions. For example, the first three lines in other versions are uniformly:

1. 掛物掛申儀次第一直ニ仕候事。When hanging a scroll, above all, it must be hung perfectly straight.

2. 同掛ひつミ仕候儀、何之床ニ而も軸先ヲ下申候。However, when hanging a scroll crooked, no matter the constitution of the alcove, the jiku-saki side of the scroll should be the lower.

3. まき板第一あをのかさるやう。When displaying a hanging scroll, above all one must ensure the maki-ita and edges of the rolled scroll are straight.

In the Kōshoji scroll, these lines come at 65 to 67. The first three lines of the Kōshoji text are:

1. 茶入ノふた。Lid of chaire.

2. 炉ノ内、小板、柄杓柄、同前盆ノ心。The hearth, small board and handle of the hishaku are all oriented with mind for the tray for the chaire.

3. 五とく、客ノ方爪一ツ、くツろきやウニ。Set the hearth’s tripod with a single leg towards the guest.

These initial lines come around 58 and 66 of other versions, which all have a variance in order by 5 lines at most. This version in Oribe’s hand is a clear exception, especially as the order difference comes from the first line. One could put it down to a mix-up when the papers were mounted on the fabric of the scroll, but this is unlikely for a scroll of one’s own composition.

The second distinct feature of the Kōshoji text is the addressee in the postscript is ‘Ōshuri-dono’ 「大修理殿」. This name has been crossed out with black ink and afterwards the ink scratched back so one can make out the original inscription 「大修理殿」‘Ōshuri-dono’. This is an abbreviation for ‘Ōno Shuri Daibu Harunaga’ 「大野修理大夫治長」a general who served Toyotomi Hideyori and fought against the Tokugawa side in both the summer and winter campaigns of the Siege of Osaka. Oribe served on the Tokugawa side in the Siege of Osaka. This document shows that Oribe had a tea disciple past enemy lines.

Some time after the Tokugawa’s victory, Oribe was ordered to commit seppuku (ritual suicide by disembowelment) under the suspicion of espionage during the Siege. The basis of this claim was that his youngest son, Kuhachirō was a page to Hideyori inside Osaka castle and that Oribe supplied information to his son during the Siege. After Osaka castle fell, Ōshuri Harunaga sacrificed himself in defeat. Following his death, it can be determined from the scroll that someone has taken Oribe’s scroll to Ōshuri Harunaga’s, undone the scroll and deleted the name of the addressee.

The Kurita-shi manuscript

This is the manuscript, if genuine, that could justifiably be called ‘Oribe’s 100 Precepts’ as its contents are unique from the other versions copied from Rikyū’s teachings. The name of reference of this version of Oribe’s precepts comes from the person who currently holds this document - Kurita Tensei of Yūsei-an, South Aoyama, Tokyo. The title on the cover reads ‘Author, Furita Oribe’「古織筆」. In the postscripts of manuscripts of 1 and 2, Oribe states clearly that he is transcribing and passing on Rikyu’s teachings. There is no mention of Rikyū in the Kurita-shi postscript. This document of 124 seperate teachings is intended for beginners of chanoyu and is dated ‘17th Year of the Keichō Era’. This translates to 1612 CE, making Oribe 69 years old at the time of composition (three years prior to his death).

English Translation

I have chosen to commence translation of these manuscripts with the Kōshoji version as it may be the only existing original record of teachings that Oribe himself wrote. As the precepts in this manuscript are much more terse, obscure and even incomplete compared to other versions, I will refer to:

- the Tokyo National Museum manuscript,

- the version published in Rikyū Zenshū entitled ‘Hundred Lines of Chanoyu’「茶湯百箇條目録」pp.144-148, which is a revised version by the scholarship of Matsuyama Ginshōan (1870-1942)

- the recently discovered “Learning from Furuta Oribe - notes from a student of chanoyu in the early Edo Period” 「茶道長問織答抄」, which is an original document composed under the auspices of Asano Yoshinaga (1576-1613). The person to have direct dialogue with Furuta Oribe and compile these notes of his teachings on behalf of Yoshinaga was Ueda Sōko.

After translating these precepts that originated with Rikyū, Oribe’s teacher, it will be of great interest to see the development of Oribe’s chanoyu in the Kurita-shi manuscript (if it is indeed genuine).

I have chosen the running English title ‘Rikyū’s Precepts of Chanoyu Transmitted by Furuta Oribe’ out of faithfulness to the original teachings, to distinguish the origin of these versions (Oribe’s copies) as opposed to the Matsuyama Ginshōan version published in the Rikyū Zenshū, and as a prelude to the Kurita-shi manuscript which may more correctly be titled ‘Oribe’s Precepts of Chanoyu’.

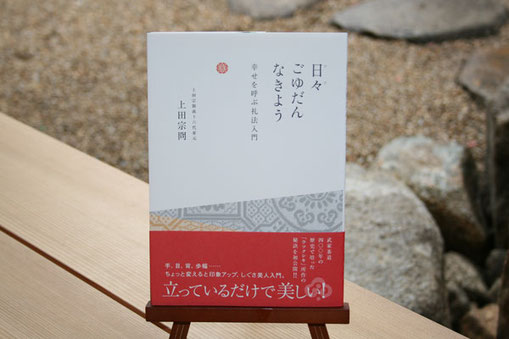

Pearl Among the Clouds

English translation: Complete, Published

by Ueda Sōkei, 16th Grandmaster of the

Ueda Sōko Tradition of the Japanese Tea Ceremony

translation by by Sōmu Wojciński

This title explores integrating the teachings of chanoyu into everyday life. In particular, it examines how the teachings of chanoyu beautify the mundane, giving a sense of fulfilment and depth to life. From posture, breathing, daily rituals like cleaning, arranging flowers, drinking tea and conversing with others, this title looks at the way chanoyu finds and promotes beauty in these everyday happenings. It does not preach that one should take up chanoyu in order to successfully integrate the teachings into one's life. Instead it offers the wisdom of chanoyu in a general context for people to remix the teachings into a form that works for them. It offers a collection of simple lessons aimed at cultivating beauty in one's life.

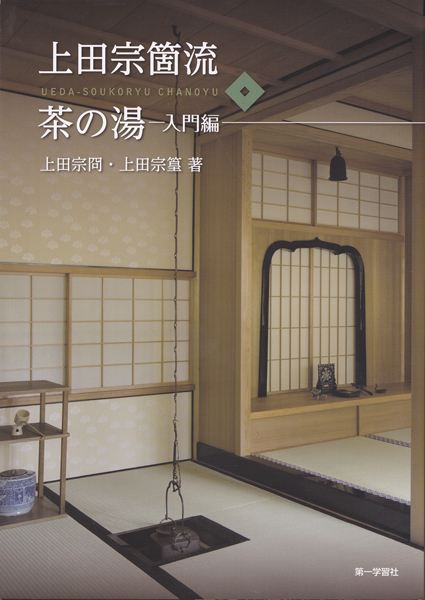

Ueda Sōko Tradition of Tea Introductory Manual

English translation: Complete, pursuing publication

This manual includes information for beginners on the history of chanoyu, the founder of the Ueda Tradition, Ueda Sōko, and it describes the fundamental postures,

actions and etiquette of the Ueda Sōko School, along with the the thin tea, thick tea and charcoal-laying temae proceedures. It also includes the chaji host and guest etiquette.

Contents

Introduction

Attitude towards practice

History of chanoyu

Ueda Sōko

Ueda Sōko's Tearooms and Gardens

The Ueda Sōko Tradition

Basic Knowledge and personal practice (wari keiko)

1. Things to prepare

2. Mizuya preparation area

3. Fundamental postures and actions

4 Seki-iri (room entering) Flow of proceedings and etiquette

5. Partaking of the Sweet and Tea

6. Equipage used in the temae

7. Warikeiko

Fundamental Temae

1. Tray Temae

2. Standard Temae for Thin Tea

3. Thick Tea Temae

4. Charcoal-laying Temae

5. Ryurei Table Temae

6. Tea Service Etiquette

Chaji Guest Etiquette

1. First Session ― Entering the Tearoom

2. Preparing the Fire for Tea (hearth)

3. Kaiseki

4. Using the Tiered Sweet Server

Preparing the Fire for Tea (brazier)

5. Intermission ・Last session - Entering the tearoom

6. Thick Tea (Koicha)

7. (Second Charcoal-laying Ceremony)

8. Thin Tea (Usucha)

History of the Ueda Clan

Grand Retainers of the Ueda Tradition of Tea

Reconstruction of the Ueda Clan Residence of Hiroshima Castle

Map of Wafūdō and Asakata-sha Shrine

After Notes

Brief Notes on the Authors

The Ueda Sōko Tradition of Chanoyu - Advanced Manual

Contents:

Section 1. The Formation of Chanoyu

The Birth of Chanoyu

The Formation of Chanoyu

- Murata Shukō

- Takeno Jōō

- Sen Rikyū

- Furuta Oribe

Genealogy of Historical Figures of Chanoyu

Section 2. Ueda Sōko

The Life of Ueda Sōko

Ueda Sōko and Chanoyu

Section 3: Mizuya Etiquette

Preparing the Mizuya

Packing up the Mizuya

Section 4: Tea Flowers

Classifying Tea Flowers

Shapes of Flower Vases

Stands for Flower Vases

Positioning Flower Vases

Styles of Flower Vases

Practical Wisdom for Arranging Flowers

Section 5: Tea Rites (including the 33 Items for Training and The 7 Items for Advanced Training)

Standard temae

- Hearth

- Brazier

- Centre-placed Brazier (Naka-oki)

- Using shelves (tana)

- Positioning Tea Equipage on Shelves (tana)

- Mulberry Small Tana (Kuwakojoku)

The three guiding principles

Tatami wale 'peaks and valleys', three divisions of the alcove, the three 'tsuyu' (tsuyu of chashaku, tsuyu of shifuku and tsuyu of hanging scroll)

Use of the seven tea caddies: Yuteki, Suiteki, Tsuritsuke, Tegame, Taikai, Oimatsu, Kinrinji

Use of the kumioke style fresh water vessel (mizusashi)

Use of the formal (shin) teoke style fresh water vessel (mizusashi)

Use of the wide-mouth fresh water vessel (mizusashi)

Protocol for host drinking tea during a temae

Thin tea temae for:

4.5 mat (yojyōhan), Daime-sized mat, Mukōgiri (opposite-side cut hearth), Sumiro (corner cut hearth), Furo (brazier), Nakaoki (middle-placement of brazier), Hongatte (standard placement of brazier), Gyakukatte (opposite orientation of brazier)

Use of water from renowned source

Hot water temae with water from renowned source

Displaying a tea whisk

Use of centre-cut tea caddy (nakatsuki) on eightfold paper

Stacked tea bowl thin tea temae

Charcoal-laying temae

- hearth

- brazier

Using a gifted bamboo scoop (chashaku)

Using a gifted tea caddy

Use of renowned tea bowls (meiki)

Using a gifted tea bowl (chawan)

Preparing tea for nobility (kinin)

Thick tea temae (koicha)

Charcoal-laying ceremony for thick tea

Charcoal-laying ceremony between thick and thin tea in a chaji (go-zumi)

Stacked chawan temae for thick tea

Use of the seven lid rests:

Hoya, Ikkanjin, Kani, Mitsuba, Sazae, Gotoku, In

Conducting tea for a single guest

Conduct of guest arranging the flowers

Conduct of guest arranging the charcoal

Conduct of guests savouring incense

Displaying a scroll

New Year's tea for health and prosperity (ōbuku-cha) temae

Conducting tea as part of a memorial service

Section 6: Guest Etiquette

Chaji

Invitation to a Chaji

Zenrei and Gorei

Items for Guests to Take to a Chaji

Chaji Guest Etiquette

First Session

- Entering the Tea Room

- Charcoal-laying ceremony (hearth)

- Kaiseki

- Charcoal-laying ceremony (brazier)

- Using the fuchi-daka sweet serving vessel

Second session

- Interval

- Entering the Tea Room

- Thick tea drinking etiquette

- Charcoal-laying ceremony between thick and thin tea in a chaji (go-zumi)

- Thin tea drinking etiquette

- Partaking of sweets

- Host farewell's guests in the tea garden (roji)

Viewing the thick tea equipage (sanki)

Viewing the thin tea equipage (ryōki)

Appendix

History of the Ueda Clan

Grand Retainers of the Ueda Sōko Ryū

Wafūdō, the Home of the Ueda Sōko Ryū